AUTHOR’S NOTE: This post was written about ten years ago. I used to have a well-received blog called Story – all about stories, of course. I packed up the blog when I packed up my entire writing life for a few years. I have a lot of articles I wrote for that blog that I never posted, and I hope to post some of them here, including the one below. Though I wrote it long before the blog ended, it never felt like the right time to post it, but with the Paralympics going, and with my niece’s husband (from New Zealand) competing there, my mind has turned to my friend Bronwyn and this post. I have rewritten it a little to adjust the timing references. My hope is that this post does some good out there in the world by sharing Bronwyn’s story now.

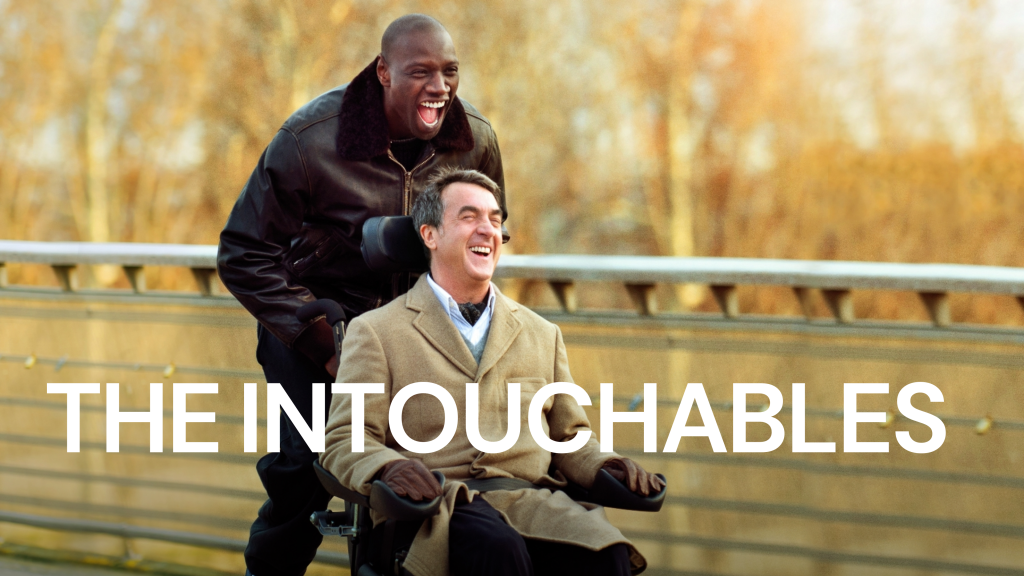

Some stories take their time consenting to be written. This one was one them. Maybe, in part, it was the grief I felt every time I thought of it. Maybe it’s because for a long time I wasn’t even sure what I was trying to say. I just knew I need to say something, but what? It took watching the movie The Intouchables to show me the message that was sitting deep inside me all that time, wanting me to find the courage to voice it.

If you haven’t seen the movie The Intouchables*, go out and hire it right now. Just go. It is the funniest, most poignant, and heartwarming movie I have seen in years – or maybe ever.

Set in modern-day France (with subtitles) it is the true story of a very wealthy upper-class quadriplegic, Phillipe (the victim of a skydiving accident), who took on the most unlikely of full-time carers, Driss – a man with absolutely no experience and from the wrong side of the tracks. A man just as uncultured as Phillipe was cultured. And why did Phillipe take on that carer? Because Driss, who hadn’t really gone after the job in the first place, didn’t look at Phillipe with pity. He didn’t see him as a quadriplegic but as a man. Between them, a beautiful and hilarious friendship forms that is a delight to watch.

The film, though utterly heartwarming, left me with that bittersweet feeling that sits somewhere between your chest and your throat. For days, I went over and over the film in my mind, smiling and yet grieving somehow. When I finally stopped to analyse what had affected me so greatly about the film, I realised that it had triggered a whole lot of bitter-sweet emotions that my good friend Bronwyn had left behind.

Bronwyn was like a little giggling pixie who saw value and wonder in everything and everyone around her. Due to an illness as a child that caused serious growth deformities, Bronwyn was confined to a wheelchair and literally as helpless as a baby. She was almost all chest perched on a motorised wheelchair that was padded out with cushions and sheepskin rugs. She had tiny, useless legs, even tinier, almost useless arms, and a small head that you often saw gasping for a deep lungful of air. To me, she was an elf, and she had a giggle that was so childlike it was contagious. She looked, in many ways, very much like a child.

She lived in her own home and had to have a carer come in every two hours throughout the day to get her out of the chair to go to the toilet, clean her house, organise food for her, or get her in and out of bed. Every night, when the last carer was heading home to her family for dinner, Bronwyn was in her specially made bed, waiting out the last hours of the day, knowing she couldn’t move until a carer came to get her up in the morning.

During the day, she could move her head a little, and only a tiny bit of her hands, enough to work the knob of her motorised wheelchair, or curl it around a pencil or a fork in the same way a baby might. Though the movement was slow, she could lift her hand to her mouth to feed herself some of her very strict diet.

But Bronwyn didn’t let her disabilities stop her at all. She lived a rich life. She read widely, she drew, she painted, she studied many courses, listened to just about every book on tape that the world had produced, and she even did editing and proofreading. Bronwyn was one of the biggest fans of my book series Bloodline. Though she did so many wonderful things, when she proofread the two books of Bloodline for me, she told me she felt she was put on this earth for this alone. I was so deeply moved. There would be hundreds of lives that she touched who would disagree, but to Bronwyn, being allowed to do that was one of the most special things she had done. She got to see Bloodline: Alliance come out in print, and we would talk for hours, dreaming together of when Bloodline: Covenant would come out. But she never got to see it.

I would often sit for hours with Bronwyn, talking science, art, books, the latest this and that, changing the world, hopes and dreams. One of her many dreams was to be a children’s book illustrator, and she did the most beautiful artwork with her very tiny, shrivelled hand. She never got to be a children’s book illustrator, though she had such promising connections, for she died quite suddenly of pneumonia before any of that came to pass. Her funeral attracted more people than I have ever seen at a funeral before, people from all over the community, each one touched by this tiny pixie lady who had the most positive unselfish outlook on life I’ve ever known.

Once, we were discussing my own health. It came out that I had suffered with debilitating pain since I was a teenager, with an illness that so far had no cure. Sometimes I was bedridden. Sometimes I wasn’t. She looked at me with such pity. “The things people go through … I’m only stuck in this chair, but you, you have it much worse.” Believe it or not, she genuinely meant it. She was just “stuck in this chair”, something that most of us couldn’t cope with for a month, let alone a lifetime.

Shortly after she died, when I was still deep in grief, I told a friend who had once known her that she had passed on. That careless friend replied, “Oh well. She had a good run. I mean, look at her. There wasn’t much left of her.”

I had no reply. I was deeply grieved by this. His words wounded me right to my core being, for to me, Bronwyn had more to her spirit than most people I knew. My beautiful friend – the one who had filled so many of my hours with sunshine – had died, leaving a gaping hole in this world, but it was the outside that this man, this friend, saw and focused on. And in so many cases with so many other people, we do the same thing.

It isn’t just the disabled. In The Intouchables, Driss (the carer) was only seen as a man from the wrong side of town, and yet he was more genuine in his depth and friendship than anyone else Phillipe had encountered. So much so, that when Driss had to leave for complicated reasons, Phillipe suddenly realised how shallow and empty and pretend his world had been, and went into a deep depression.

Everyone, bar none, has more to their story than what they look like on the outside. And yet too often we stare at the covers of a story and say to ourselves, “There’s not much to it.” Or, “Well, that looks a little uncomfortable or trashy. I’m not sure I want to open that one.” Or perhaps even, “That story isn’t for me.” And from there we decide we’ve seen enough. We ignore the thousands and thousands of pages hidden inside the covers that make up that story because we’ve convinced ourselves that either there aren’t any pages to that story, or the few we believe are there aren’t much good.

But pages there are! Many, many pages. And when you do bother to find out more about someone’s story, sometimes the most unlikely stories – the Bronwyns, the Intouchtables – are the ones with the most to teach us, and the most ability to enrich our worlds. The ones with the best stories of all. ▪

* There is now an American (English speaking version) called The Upside, which I also watched. You may prefer it, especially if you don’t do well with subtitles, but the original will always have that special place in my heart.