Short on time? Maybe jump straight to “Why I’m admitting this now.”

I just want you to know that if you suffer from mental health issues, from depression, you are not alone. You. Are. Not. Alone.

I also know that if you are currently in a deep depression, you believe you are alone and nothing I say will convince you otherwise. A thousand people can jump up and say, “I suffer too” and it won’t make a scrap of difference. When you are depressed, you feel alone. You feel utterly, inescapably trapped within yourself. Your body is just a mask you wear and a prison. And no one can get past it to reach you there. No one really understands what you’re going through. That’s what you believe, and there’s no convincing you otherwise. To be depressed is to be alone. I know. I’ve been there. I am there.

I am, and have been for as long as I can remember, what they now call a high-functioning depressive. That is, on the outside, I can look like I am coping. I can still mostly function, but on the inside, I am suffering from depression. On top of that, though, I suffer from at least one depression every two years that is debilitating. I cannot work. I cannot talk. I struggle to get out of bed. Have a shower. Eat. Read. I sit in a chair all day and stare at the wall – literally. I withdraw from life itself.

I was made to visit a psychiatrist during a very severe episode while I was pregnant with my son over eighteen years ago now. While I was there he asked me, had I experienced more than two or three depressions in my life because that constituted a mental health issue. I remember feeling disoriented by the question because I had a minimum of two or three depressions per year! The psychiatrist informed me that the amount of depressions I got in my lifetime just wasn’t normal. I had never heard before that even one bout of depression a year, year after year isn’t normal. I just assumed everyone went through at least one yearly. To me, having one every few months, with at least one very major one every two years (as I did) was just a slight step up from the normal or what I thought everyone else was experiencing. I still didn’t think of myself as having mental health issues. The term “mentally ill” just didn’t feel right – and certainly had an ugly stigma I wasn’t willing to wear – because there were times when I was “normal” or what I thought was normal. I just had a few downtimes every year.

It took me a long, long time to admit that I suffered from mental illness. Illness. As in not a state of wellness. It took me all the way until about four years ago to my second English winter. And when I did, because I was going through one of the very worst depressions I’d ever had thanks to a severe case of Seasonally Affected Disorder, I realised that it was freeing, in a way, to admit that I had suffered with it my whole life. It was like any other physical illness or lifelong health issue. Once you name it and you accept it, you can manage it.

If you are told you have Type-2 Diabetes, you have to manage it. You have to make sure it doesn’t keep creating health problems. Your lifestyle must adjust. Your eating must adjust. You boost yourself with vitamins and with exercise and with anything else that you can grab hold of. There are times you have to say, “I can’t do that today, because I am unwell.” Or times you have to let go of things because at that time in your life you know your health must come first. There is no shame in this. It just is.

If you have mental health issues, you have to do the same. You have to manage it. It’s a part of your day and week and must be considered now in how you live your life. Once I realised that, I discovered ways I could cope, preventatives, and so things started to get better. I was not cured, but I could manage the problem now.

But managing it becomes a daily routine. And sometimes, when I am sliding into the darkness, it becomes a full-time job. At such times, it becomes the only thing you can do and must do or you will fall into a deep state of depression. And managing it, even if it’s a habit, isn’t always easy. Sometimes it’s downright hard. I suppose it’s rather like knowing you need to exercise every day to manage diabetes but sometimes getting up at the crack of dawn, getting on your sport gear, and going out into the cold for a run before coming back for a shower and starting your day, is hard work, and you forget how much harder it is if you let the diabetes overtake you. You convince yourself that exercise is just all-too hard and so you rest for a while. That’s what it feels like: rest. But in the end, it’s not a rest at all because you become sicker. And the sicker you become, the harder it is to get into the exercise again. It’s a much, much higher climb towards good health and an exercise habit than if you’d just kept jogging every morning.

That’s what mental health is like. In fact, let me put it this way:-

Imagine this.

You are hanging off the edge of a cliff by your hands. Beneath you is a giant cavern of blackness. Above you on the very cliff edge – if you can get your feet to stand on it – is normality. Once at the top, if you could push further from the cliff edge along the plateau and begin another climb, you might even experience some of that elusive goal of vitality and energy and a feeling of abundant life. But you rarely get more than a glimpse, if at all. You never truly feel happy, but you can feel not depressed, and that’s what the fight is for.

But right now, the goal is just to stop yourself falling. Even basic normality, that plateau, feels elusive too. You are so tired. Your arms are exhausted, but you know that to let go is to fall into that blackness and if you do, it’s a much, much harder, longer, more exhausting climb. In fact, when you fall down there, you usually can’t see a way to climb out at all. So you usually sit down in there and stop trying and you believe that life will always be this way, that there is no hope or joy left, and that death seems so much better. You can’t even remember what it’s like to be up there on that plateau. All memory of happiness is gone.

In some ways, that black hole can give the illusion of a rest because you stop fighting for a while. Yes, it’s horrible, dark, draining and dank down there – and it’s the loneliest, lightless place on earth – but at least you can stop fighting. It would be so easy to let go. But then, there’s that hope that awaits but for the last push towards the top. You are closer here to that hope, if you can just cling on, but it’s a full-time job doing so. It requires every bit of concentration and effort you have. You lapse for even a second and your fingers will let go and you’ll fall.

Sometimes you can spend most of your life hanging there like that, trying not to fall. Sometimes you make it to the top but always and only ever at the cliff’s edge. You plateau emotionally on that plateau. True happiness is something you can see at a distance and never seem to reach. You know there’s more, but you are somehow incapable of ever experiencing it. That requires another climb you just don’t have the energy or ability for. It takes all that you’ve got just to get to or stay on the plateau. Everyone else (or so it seems) is way off into the glorious, majestic mountains of that full life that is beyond that cliff edge, but every time you try to go after it and them, something knocks you off the climb and you slide back into your place. The plateau, though – this more awake, aware and functioning place – is still worth the climb, even if full joy and happiness eludes you. When you get to the top, you realise the lie that falling to the bottom is easier and a rest. Being at the top, on your own two feet, and feeling a kind of happiness again, is energising. The “rest” at the bottom of depression will sap you of all the strength and vitality you have.

The fall, though, is never far away, even when you know how much better the plateau is. When you are someone who is chronically depressed, those better times of your life are lived by the cliff edge whether you want to move on or not. And it only takes the slightest nudge and you are back to hanging off the cliff wall by your hands again. And every day becomes that fight to stop yourself from falling.

And that is what it is like. That is the reality that I face. And perhaps you face it too, or perhaps you would describe it differently to me, and that’s okay.

Things that cause the fall.

One of the realities of being someone who suffers from depression, is that it doesn’t seem to take much to knock me to the edge of the cliff or over it. Sometimes it can be the tiniest thing.

I know I don’t have a filter that allows me to protect myself from what goes in. It all goes in. And I don’t have an easy way to just discharge any of it when it gets there. It almost all builds up and some things stay for decades with almost the clarity of when it first happened. Sometimes, for instance, I get flashbacks from really rather insignificant but unpleasant things that happened years ago. A throwaway but hurtful comment in a conversation, for example, might re-surge in my mind as clearly and unpleasantly as if it happened a week ago, and it’ll trigger a tumble where I’m clinging to the edge of the cliff again. So it might not even be something happening in the here and now. I suspect now, after decades of dealing with it, that the flashbacks come because I’m heading for another depression, maybe not the other way around, so perhaps, too, I just don’t have the right chemicals in my brain needed for feeling happy enough to take the knocks and blows that life inevitably brings. I don’t walk around thinking negatively all the time. If that was the cause of all the problems, I could just try positive thinking – which I practice as much as I can – and all would be well.

For me, one of my biggest triggers and the one impossible to avoid is that I am highly sensitive to light. The wrong light for too long, and by too long I mean a few weeks or sometimes even days, and I am back to hanging off the cliff. Winter here in the UK, for instance: if I don’t heavily manage it, I am in the black hole, and I cannot get out then until the light changes. And before you say, “But you moved to Scotland,” it happened to me in summer in Australia too – the light on a sunny day was too bright, too intense, and it too caused depression. I had to close the curtains to cope but that meant a winter-like darkness. Though I found winter easier than summer, I had Seasonally Affected Disorder mildly over the Australian winter months too. So it hit me twice a year.

It has taken me a long, long time to learn what helps me get back on the plateau or helps me cling to the cliff edge longer. I have even found myself stepping beyond the cliff edge of late and climbing the mountain of genuine happiness a little way up so that it takes a bit more to put me back there. Light therapy in winter, for instance. I have learned that taking very high levels of Vitamin D (10,000+ mg) is essential for combating the long, long winter months and the extra winter-like months (think winter that can go all the way to summer’s edge) here. Alpha-GPC has been a lifeline for getting my brain to a level of vitality I never thought possible. Within an hour of taking it, it’s like I woke up for the first time since my early twenties, and I realised how deep into the darkness I had been living all this time. With that highly positive beginning, my brain vitality has been increasing ever since. It works so well, I wonder if maybe whatever it fixes could be a deficiency in many with chronic depression. St John’s Wort is my vital boost in the winter months when even with all that I do to ward off depression, the chemical imbalance caused by the lack of light just becomes too much to outweigh. That’s when St John’s Wort is my extra support.

I have learned that when I have been sliding towards the cliff edge, stopping every afternoon at the same time of the day to do an activity that requires minute details can really help. A cross-stitch by the window. A paint-by-numbers or a colouring book with really small details in it. (Studies do show that highly detailed work, having to concentrate on little tiny details, can counteract depression.) Or stopping to read a good, escapist and uplifting book, or maybe even making reading that book my full-time job. Reading illustrated poetry books or going through my collection of beautiful children’s books. Eating a piece of dark chocolate every afternoon at the same time, with a cup of tea in hand, for the magnesium and zinc and for the calming routine of it. Every afternoon in the winter months, after the sun goes down at 4pm, I watch an online documentary or re-runs of TV series right up close to my computer screen to give me a feeling of extra light in the day and to fill in that long, dark hour after the sun goes down and before I have to start the dinner. It becomes a treat that makes me look forward to the light going down instead of despairing – a trick I have learned. Then there’s cutting back on all but the necessities in my day. Going quiet for a while and avoiding confrontation or sources of negativity such as the highly toxic internet and world of social media. Avoiding certain movies or entertainment. And, most importantly, getting into art more and doing art journaling. My art has been, perhaps, the biggest saving grace for me because it gives me words and expression and a way to go deep, deep, deep into the flow state that helps me to feel lighter and more energised when I am done.

Everybody is going to have those few things that really help. The point is to make them a routine, a habit, before habit-destroying depression comes upon us and tells us that it’s all hopeless and pointless and that there’s nothing that will ever help. Believe me, it is so easy to accept that lie when you are in the black, lonely pit.

Why I’m admitting this now.

I just made it through one of the most brutal winters I had ever endured, now that I am glamping in the wilds of Scotland … having followed God here. (I add that last part so you don’t say, “Why, with your mental health issues, are you doing that?”)

Despite blow after horrible blow, day after day, I fought back a depression that could have overwhelmed me, with the help of my two most amazing vitamins from a vitamin company I absolutely stand by. My very high Vitamin D I mentioned and my Apha-GPC. I didn’t always feel great, but I know that I stood mostly very strong compared to where I could have been even without the hardships of the winter. (As I said, it doesn’t take much to knock mentally ill people off that cliff.)

But then something went wrong with my re-order of my vitamins just a few weeks ago, leaving me entirely without. (As I write this they still haven’t arrived.) Winter came back with a vengeance, despite it being April. Snow. Gale force winds. Power cuts. And on and on. And then our building began and, like it has been since we arrived here, it was one compromise, one disappointment, one heartbreak after another.

And within the space of two weeks, I was hanging on by my fingernails, except I wasn’t at the cliff edge anymore, I was on a ledge somewhere just above the pit. And after a year of feeling a few levels above okay, I realised how very, very bad I used to get. The pit is so much darker, deeper, and inescapable after you’ve experienced the joys of the plateau and even beyond the plateau towards normal and actually happy for so long.

And suddenly, like struggling with exercising if you’re a diabetic, I couldn’t paint. I knew if I could, I would feel better, but I couldn’t push past the barrier in my mind. I was trapped inside my body and couldn’t make it to my hands to get them to draw a picture ready for me to paint. And I believed that I would never paint again and my painting days were over. I couldn’t even remember how I had painted anything that I’d already done. It felt like someone else painted them. I actually said to myself, “I’ll never be that good. I can’t paint like that.”

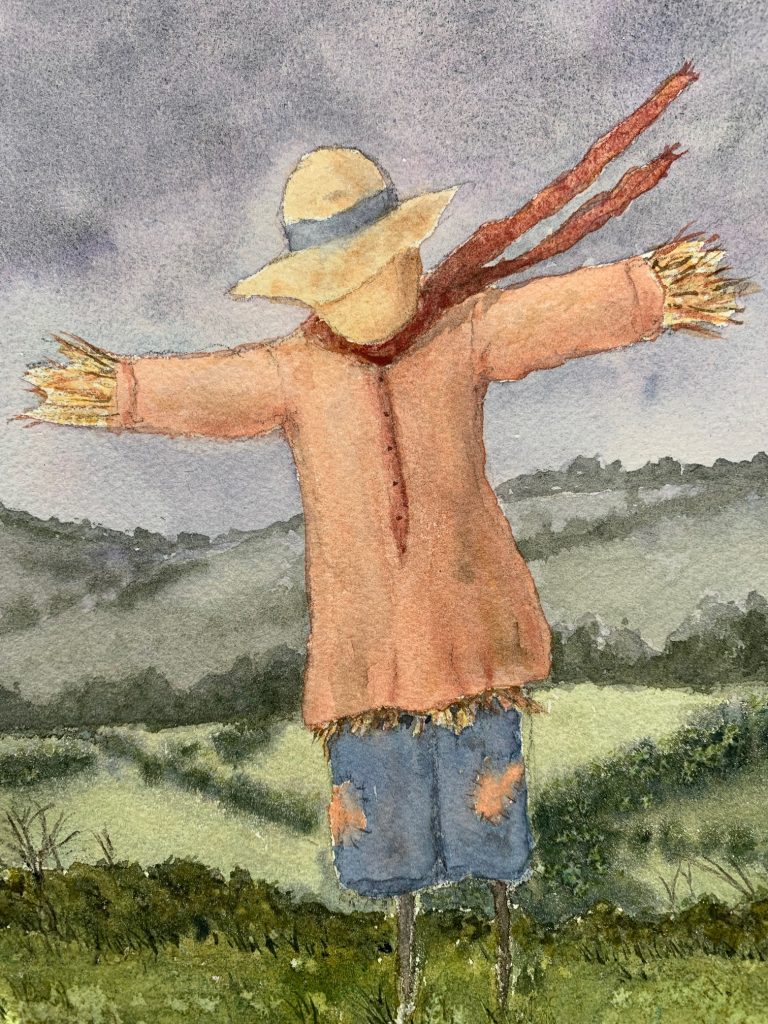

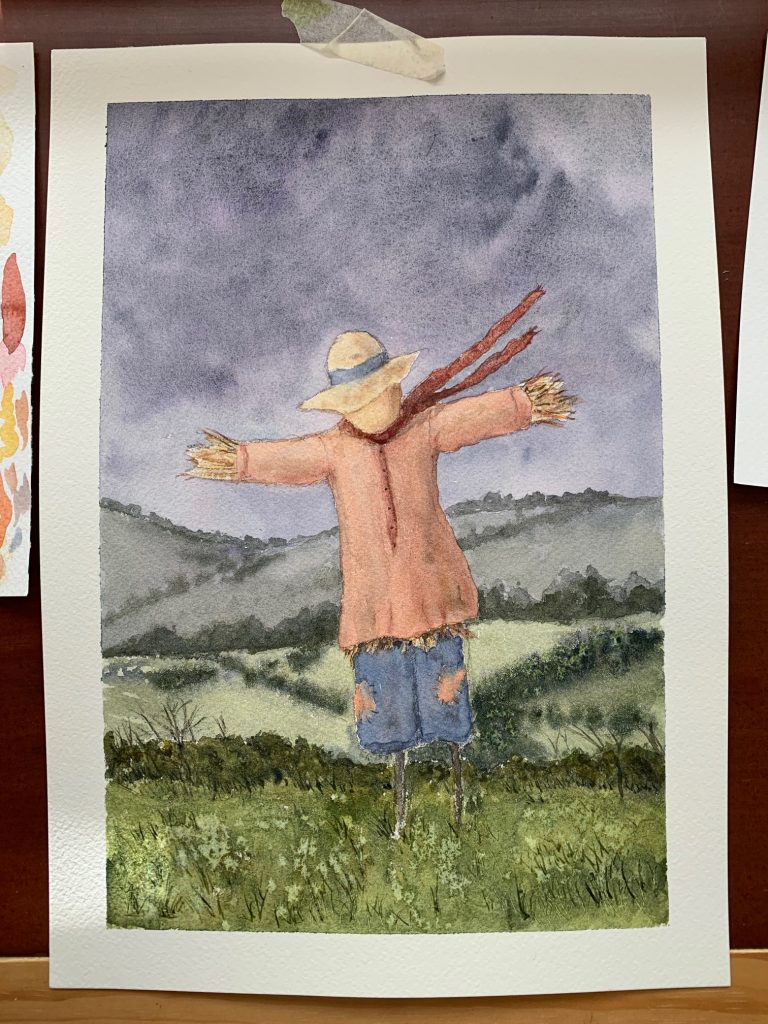

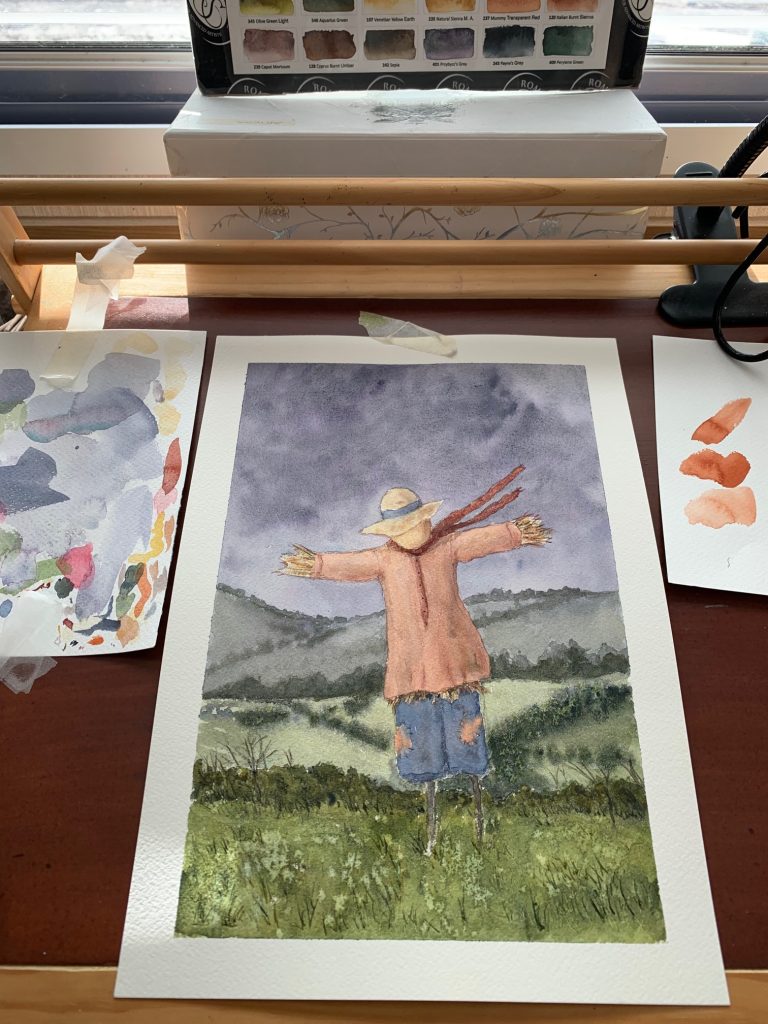

But I first began painting as a way to express myself when words wouldn’t come, and I knew that once again I needed to express something that was happening inside me, some reality. I couldn’t put it into words what it was, but the image was out there. I kept thinking, “Scarecrow. I need to paint a scarecrow.” A very particular kind of scarecrow in a very particular kind of scene. The need became so strong, I was able to push through the wall of resistance and paint it. And as I did, I knew why I had to paint it. It’s because to me, somehow, it expressed what it was like to be someone with high-functioning depression.

If you look at this painting and you think, “That is sweet,” that’s the right response. I painted it to be sweet. It’s a whimsical little scarecrow in her pretty little patched clothes, against a lovely pastoral scene. I want it to be a nice painting on the surface. But like much of my art, and exactly like someone with high-functioning depression, the closer you look, the more you see.

This scarecrow is what it looks like to me to suffer with this mental illness. You never quite feel normal, not like other people. It’s just an illusion of normal. A trick. Inside, you’re made up of things that aren’t quite right and aren’t what you’re supposed to be made of. You’re meant to look normal, you’re meant to represent a human being, but you never quite feel like one. And you are alone. You stand outside, by yourself. And you are trapped there. You can’t seem to imagine a way to escape this reality. Your mental “legs” don’t really work the way legs should. You can’t walk away from this place. This is where life has put you. This is where you are. This is who you are. You have a purpose ordained by God, yes, but that purpose is to stand alone, away from “real” people. And even in your purpose, you feel forgotten. Look at the grass the scarecrow is standing in. It isn’t even a wheat field or corn field anymore. It’s just overgrown grass and small scrubby weeds where the furrows of crop used to be. You were placed here but feel forgotten, abandoned, overlooked. You’re not even doing what you were made for.

Look at the elements. You feel battered by them, by the strong wind blasting you and the storm clouds gathering or retreating behind you. But there is light there too, patches of light against the darkness behind you. Small times of light can brighten you up, but in the end, you are still just that lonely scarecrow, still stuck in that place, still outside of all things and different. You have no real face. Your face is a mask. You feel nameless, unknown, and there is sadness there. See the way the head droops and the featureless face is downcast? Yes, look closer, and you will see the sadness and weariness there.

That is how this feels. And that is what I had to paint.

I thought of a thousand titles for this piece. Normally titles come to me almost straight away because I know what my art is about and why I painted it. But this time, no name felt right because they were all right and yet not quite right. It was a picture that both told and hid a thousand words. And so I realised that its title is just “Scarecrow” – a name that masks a thousand names, just like the outward appearance of a high-functioning depressive masks the true and complex reality of their experience.

If you struggle with this too, then I say it again: You. Are. NOT. Alone. And I hope that in some small way I have made you feel understood. And if you don’t suffer from this but have read this far, I hope that in some small way this will help you understand someone else who is going through this. To all those who support someone who suffers from mental illness, you too, are not alone.

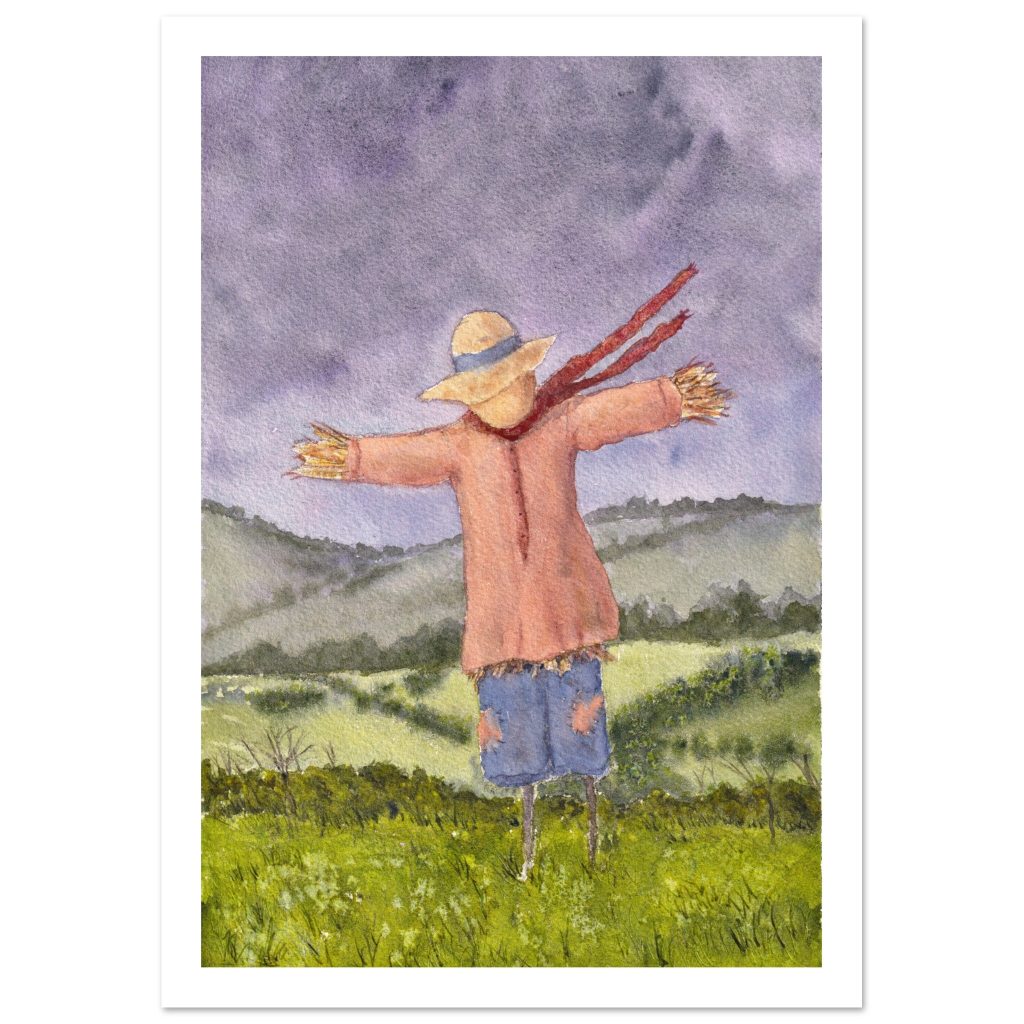

Scarecrow, the print, is available in our Willow Lane shop if you’d like a copy. We ship worldwide and 10% of all our profits go to fill a need we see.

CLICK HERE

Who are we? We are just two sisters with a passion for art and design. Willow Lane is the place where our art and design meet.