The special burden of being a writer – the good and the bad of the writing life.

My teen son, Tristan, sits on a comfortable reading chair in the corner of the room, the grey English autumn light illuminating the pages of his book. He is reading The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken.

I sit in the farthest corner to the window, my phone in hand, looking up something I need to research.

Tristan lowers the book briefly. We have just watched the movie Frozen the night before and he mentions the scene where the wolves attack the sleigh. He tells me that the book he is reading has scenes like that too.

Curious about the book, while he is talking I look it up online and the first thing I read on Wikipedia, before anything else about the book, is that the author, Joan Aiken, took a long time to write the book, even taking a seven-year gap in the writing. The sentence reminds me keenly of long gaps in my own writing that were filled with struggles.

Just as I read it, Tristan tells me about the new introduction that Joan Aiken’s daughter wrote for this latest edition. She apparently talks about how much of a struggle it was for her mother to write that book even though the daughter didn’t realise it at the time.

Tristan finishes with: “Just like I don’t realise how much of a struggle your books can be for you to write.”

I think about the many, many years I took off from writing after it drained me to emptiness, and the many, many years before that when I wanted to quit but kept picking myself off the floor of pain and sadness. The thought of Joan Aiken struggling too, causes my mind to wander old roads of all the burdens writing brings with it for many writers. I am expecting twinges of pain or the inevitable heavy weariness as I dredge up all the negatives again.

It’s not just the long hours with no pay or with no guarantee your book will ever be read by anyone. Or the long hours alone. Or the battle with self-motivation at times. Or the publishing rejections. Or the way we must face the criticism and derision of others through our brave new world of reader reviews. There are so many difficulties that come with even just having a writer’s mind.

* To be a great writer, you need to have a gift of empathy. That means that you can know exactly what a person would be thinking and feeling in any given situation. You must always be able to put yourself in another person’s shoes. Actors have to do it too, but writers have to do it to an even deeper level because we have to be able to articulate every thought process, every emotion, every physical response, every reaction, and be able to weave the hardships, struggles, past, present and future of many, many characters in every single book. To some degree, we have to be them. That means we have to not only know what they would be feeling, but feel it too in order to describe it. For weeks and weeks and months and months and sometimes years and years, we sit with these broken, dysfunctional people – goodies and baddies – and we have to go through what they’re going through to write it down, and all without losing ourselves in the process. I know I sometimes do lose myself. I become vague. I hear characters talking to me and to each other when I’m not even at my desk. After particularly draining scenes, I sometimes go quiet for days. And that’s only the first draft. I may have to re-read those scenes over and over.

* We don’t just notice what other people think and feel. We must many times call on the darkness, brokenness and pain within ourselves. If I write, for example, a scene where a character has been stabbed, I must call to mind something that felt like a sharp stabbing pain within me to describe it and convince the reader of that experience. If I write a scene where a character is abused and broken and feeling small and childlike, I must call to mind those times in my childhood when I felt the same in order to describe it now. I must go with my own life experiences with the things that have troubled me, wounded me, angered me, in order to call up story messages and themes and ideas that make my books about something and make them meaningful.

* As writers, we tend to always be on the outside looking in. We are observers. We observe our world, and we especially observe people. We tend to be readers of body language, of tones of voice. We are assessing a crowd of people for deeper truths of what they are thinking and feeling, and we are listening for stories and ideas or asking people questions to get to the heart of matters. If we were on the inside taking part, we wouldn’t be able to see all of that. We would be too busy participating on that superficial or deceptive level. Imagine a pool party, for instance, where you are supposed to be having a whole lot of fun swimming, eating great food and drinking great wine while the energising music plays. You can only really do that if you let go and stop seeing the teen boy in the corner of the courtyard who is shy and sad, or the woman who doesn’t seem herself that afternoon, or the overly confident man who is definitely hiding his insecurities, the person in the conversation who just oddly seemed to give a deceitful answer about something she did this week, or the friend who is drinking too much and seems to have been doing that more of late. To see the deeper issues, we must step back and observe, not disturb. And that means that we are never really a part of things, even as we are there participating. It can be lonely, but it can also be a gift, because we can truly see people as they are and empathise and have compassion for them.

* A friend of mine is a screenwriter and she gave me an illustration one day that summed up what the writing process can be like: “Our mind is like two rooms, the front room and the joining back room. We must go all the way to the back room to get what we need to write. In order to do that, we have to run through the front room where voices are there jeering at us and shouting at us and telling us that you are terrible at your job; that the page you just wrote is really bad; readers aren’t going to like your work; you’ve lost your skills; or what would your mother think if she read that love scene?”

I laughed as she spoke because I knew what she was saying. The brain, as you know, is divided into the left brain and right brain. The left brain is the verbal brain – it’s responsible for words, for conversations, and for naming things, describing things, and it’s the more conscious brain. The right brain is the artistic, creative, drawing brain and the deeper imagination. It’s the hemisphere we slip into when we go into “the flow” or the state where time seems suspended, creativity is flowing, and we are energising ourselves. We all have those voices of doubt, those negative voices that we must wrestle with, but when it comes to work and other artistic forms, we can usually push them to the back of our left-brain minds and deal with them later, or manage them briefly in order to get on with the task at hand. Those voices are like conversations going on with ourselves or with imaginary people who we manifest to doubt us and question us.

To imagine places and people, to be deep in the moment, we need to be in the right hemisphere of our brain, or the back room. But to write, and to especially think up and write conversations, we need a wide-open left brain or the front room. We can’t switch the conversations and language part of our brain off. We need it. Not only is writing all about language, but we must be hearing conversations throughout our writing. Hearing voices is part of what we do. Or we have to be able to take a piece of imagination and decide how to describe it. Deciding how to describe something is distinctly the left brain’s domain. So we pull up imagery from the back room and then sit in the front room with all those voices and try to block out the wrong ones to hear the ones we want to transcribe.

We are constantly running back and forth between those two halves of the brain or those two rooms, and quite consciously at times. And to do so, we have to run past all those voices that other people get to switch off. We have to leave the ability to have conversations and to hear voices wide open. Sometimes we don’t make it past the voices, or we believe those voices for a while, or we get to that backroom and find we’ve been locked out: the dreaded writer’s block. When that happens, the voices can sometimes get very loud telling us we’ve lost the skills now, we were never that good, we’ll never write again, or our last book was our best work ever and it’s all downhill from here. And added to that is the issue that the voices get louder and more numerous the more years we write. Doubts and negativity only tend to grow the more professional and purposeful we become.

* Because of the way our writer’s brains are made, many writers live without filters to protect us. Everything goes in. We don’t seem to have a way to filter or shut out some of what is happening around us. We have deep empathy and keen observational skills and memories built for stories and for facts, clues, insights and other material we might use. And we are deeply aware of our senses and what is happening in any situation, whether we notice it on the spot or can easily recall it later when we have to use our experience to describe a scene. We are emotional magpies picking at the piles of information, sensory experiences, emotions, and memories that are accumulating over years and years in our brains in the hope of turning it into a character, a dramatic experience, an inner monologue, a description, a story, a novel. For that reason, I am guessing that many writers are introverts. Introverts who love people. We are fascinated by people, and we get lonely, but we also need long periods of time alone in order to protect ourselves and to process all the things that bombard us from the outside world. We love to sit and write alone for long hours or read for long hours and yet we can get terribly lonely doing that too because people are our business. We are always thinking of our readers, our audience, our tribes, and yet we are disconnected from them. We don’t get to sit with them in meetings like say, an interior designer does, and show them our mood boards and get their feedback, then work on-site with them to see the design fulfilled. But we must be as aware of our readers, our clients, as any designer is. And sometimes our only company can be negative reviews or criticisms we’ve received in the past, or our own doubts and those voices in that room in our mind.

* Our work can be a way to constantly relive, reuse or recycle our negative and painful experiences. Life experiences enhance our writing and become our writing, even if they are totally unrecognisable from our past, such as in a fantasy novel. But we have to call on those experiences in order to create the themes of our books, the depths of characters or lack of depth in characters, the wisdom we might call forth in our books, and the descriptions and experiences of characters. So our job must always be reflective and introspective, no matter how difficult and painful that can be at times. Nothing is wasted when you are a writer, and in fact, it is the darker times of our lives that are worth the most when it comes to writing powerful, moving and world-changing books. Sometimes it can be like having a job where you sit with a psychologist every day and mine your past for problems in order to turn it into hope and change. Sometimes it is rewarding and freeing, and sometimes it is draining, unfinished, or painful.

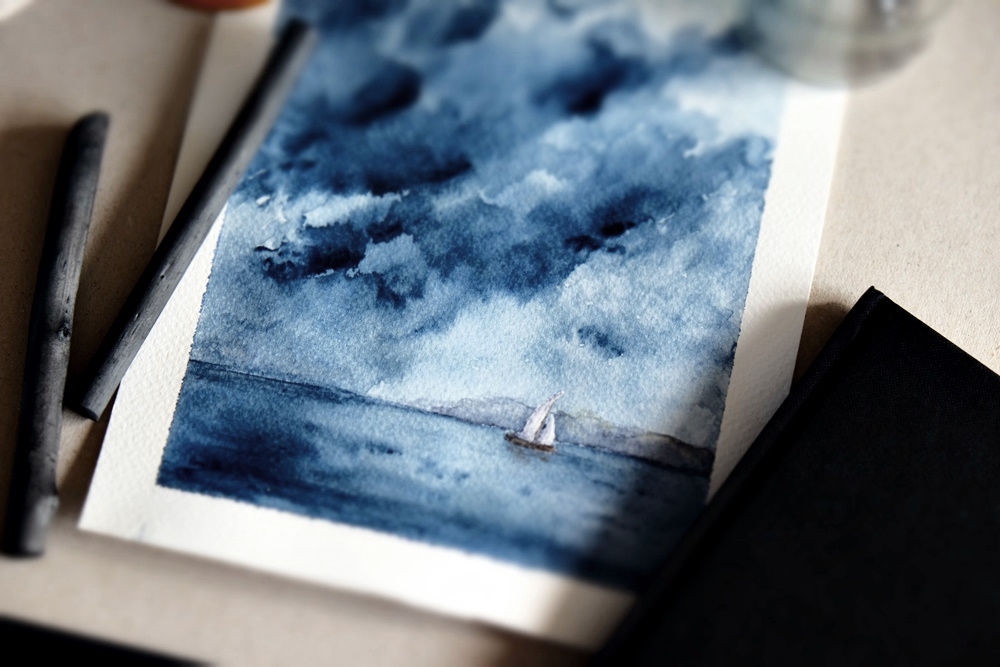

Given all of that, is it any wonder then that writers are at a greater risk of mental health issues than any other creative profession? One of many studies on the subject, a Swedish study involving almost 1.2 million people, found that writers have more than double the risk of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety and substance abuse. The study also looked at other creative careers but found that other artists were only at a greater risk for bipolar disorder and not for all the other issues, and even this was a much much greater risk for writers compared to other artists. I can tell you from experience that when I do my photography and my watercolour art, I am energised, alive in a very different way to writing. I feel I have escaped the problems of the world and can emerge fresher to deal with it. Not so writing. That’s because when it comes to writing, I have to face the problems of the world and dig their depths.

I have experienced the writer’s high many times too, but when you have to pair that with sitting in the dirt and despair of the world or tapping into the deep recesses of experienced pain day after day to create meaning in my writing and depth in my characters, you can see how writing is a special kind of suffering for our art. Unlike most other art forms, writers don’t have a choice about whether we draw inspiration from suffering or not. It is a tool of our trade. Even comedy must to some extent draw from the dysfunctional or the ridiculous.

Tristan’s words sit with their weighty presence in my mind for a while. “… Just like I don’t realise how much of a struggle your books can be for you to write.”

“Yes,” I say after a while. “There is a special burden that comes with being a writer.”

The word “special” triggers something in me that isn’t the usual twinges of pain or weariness. A new awareness comes over me then: the specialness about it all. Special. I think I mean ‘sacred’, ‘blessed’. Yes, that feels right. It’s as if I see God looking down and seeing the tenderhearted ones and saying, “That one, she is special. She is set apart. I need that tender heart. She will be called out to be my special writer, and through her empathy we will change lives. I will keep her separate, held in my hands, so she can see all that goes on around her … and we will touch lives together.”

Tristan gives a firm nod. “I guess the moral to the story is: don’t be a writer.”

I can see that outsiders would wonder why we keep choosing it. I think it’s more that it chooses us. Or rather, God calls us to it. Writing is who we are at our core as much as any other aspect of our personality. To switch it off is like telling an extrovert they can no longer be around people. It’s soul-destroying. I am reminded of the humorous quote by Anne Lamott in her wonderful (and recommended) book Bird by Bird:

“One writer I know tells me that he sits down every morning and says to himself nicely, ‘It’s not like you don’t have a choice, because you do – you can either type or kill yourself.’”

Something in us is deeply drawn to writing and we cannot ignore that call even when we try to quit. I know, because I quit many years ago, and I mean QUIT, packed up all of my writing and pulled my books off the market, and yet not even two months into that horrendously painful divorce, my novel Shadowland poured out of me in the space of two weeks.

I have often thought about the pain and struggles of being a writer and thought, “If I could be anything else, I would not be this.” It was as if being a writer meant being the one overlooked by God, the one forgotten, the one left out. Especially if I didn’t see sales to match the struggle and huge emotional cost of writing a book. But as I am sitting here thinking about my son’s words and mine, I realise that the calling to be a writer and the calling to carry the burdens of a writer is actually a very holy – very set apart – one. “… that one, she is special. She will carry my heart.”

We are not overlooked, left out, forgotten. We are deliberately called out of the crowds to be separate from others, always on the outside looking in, so that we can see the stories around us, feel the pain around us, see and feel the struggles of our time, and then translate that into stories that change our times for the better, even if we are called to write the happy books that bring much-needed laughter to the lives of others. It is a sacred and holy calling.

“Well, sometimes that is who you are called to be,” I tell Tristan. “And so you must be it.”

***